Josephson effect

The Josephson effect is the phenomenon of supercurrent — i.e. a current that flows indefinitely long without any voltage applied — across a device known as a Josephson junction (JJ), and consisting in two superconductors coupled by a weak link. The weak link can consist of a thin insulating barrier (known as a superconductor–insulator–superconductor junction, or S-I-S), a short section of non-superconducting metal (S-N-S), or a physical constriction that weakens the superconductivity at the point of contact (S-s-S). The term is named after British physicist Brian David Josephson, who predicted in 1962 the mathematical relationships for the current and voltage across the weak link.[1][2] Before his prediction it was only known that normal (i.e. non-superconducting) electrons can flow through an insulating barrier, by means of quantum tunneling. Josephson was the first to predict the tunneling of superconducting Cooper pairs. For this work, Josephson received the Nobel prize in physics in 1973.[3] Josephson junctions have important applications in quantum-mechanical circuits, such as SQUIDs, superconducting qubits and RSFQ digital electronics.

A Dayem bridge is a thin-film variant of the Josephson junction in which the weak link consists of a superconducting wire with dimensions on the scale of a few micrometres or less.[4][5]

Contents |

The effect

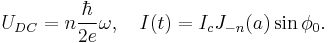

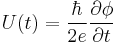

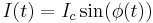

The basic equations governing the dynamics of the Josephson effect are[6]

(superconducting phase evolution equation)

(superconducting phase evolution equation)

(Josephson or weak-link current-phase relation)

(Josephson or weak-link current-phase relation)

where U(t) and I(t) are the voltage and current across the Josephson junction,  is the "phase difference" across the junction (i.e., the difference in phase factor, or equivalently, argument, between the Ginzburg–Landau complex order parameter of the two superconductors composing the junction), and Ic is a constant, the critical current of the junction. The critical current is an important phenomenological parameter of the device that can be affected by temperature as well as by an applied magnetic field. The physical constant h/2e is the magnetic flux quantum, the inverse of which is the Josephson constant.

is the "phase difference" across the junction (i.e., the difference in phase factor, or equivalently, argument, between the Ginzburg–Landau complex order parameter of the two superconductors composing the junction), and Ic is a constant, the critical current of the junction. The critical current is an important phenomenological parameter of the device that can be affected by temperature as well as by an applied magnetic field. The physical constant h/2e is the magnetic flux quantum, the inverse of which is the Josephson constant.

The three main effects predicted by Josephson follow from these relations:

- The DC Josephson effect

- This refers to the phenomenon of a direct current crossing from the insulator in the absence of any external electromagnetic field, owing to tunneling. This DC Josephson current is proportional to the sine of the phase difference across the insulator, and may take values between

and

and  .

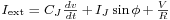

. - The AC Josephson effect

- With a fixed voltage

across the junctions, the phase will vary linearly with time and the current will be an AC current with amplitude

across the junctions, the phase will vary linearly with time and the current will be an AC current with amplitude  and frequency

and frequency  . The complete expression for the current drive

. The complete expression for the current drive  becomes

becomes  . This means a Josephson junction can act as a perfect voltage-to-frequency converter.

. This means a Josephson junction can act as a perfect voltage-to-frequency converter. - The inverse AC Josephson effect

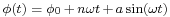

- If the phase takes the form

, the voltage and current will be

, the voltage and current will be

The DC components will then be

Hence, for distinct DC voltages, the junction may carry a DC current and the junction acts like a perfect frequency-to-voltage converter.

Applications

The Josephson effect has found wide usage, for example in the following areas:

- SQUIDs, or superconducting quantum interference devices, are very sensitive magnetometers that operate via the Josephson effect. They are widely used in science and engineering. (See main article: SQUID.)

- In precision metrology, the Josephson effect provides an exactly reproducible conversion between frequency and voltage. Since the frequency is already defined precisely and practically by the caesium standard, the Josephson effect is used, for most practical purposes, to give the definition of a volt (although, as of July 2007, this is not the official BIPM definition[7]).

- Single-electron transistors are often constructed of superconducting materials, allowing use to be made of the Josephson effect to achieve novel effects. The resulting device is called a "superconducting single-electron transistor."[8] The Josephson effect is also used for the most precise measurements of elementary charge in terms of the Josephson constant and von Klitzing constant which is related to the quantum Hall effect.

- RSFQ digital electronics is based on shunted Josephson junctions. In this case, the junction switching event is associated to the emission of one magnetic flux quantum

that carries the digital information: the absence of switching is equivalent to 0, while one switching event carries a 1.

that carries the digital information: the absence of switching is equivalent to 0, while one switching event carries a 1.

- Josephson junctions are integral in superconducting quantum computing as qubits such as in a flux qubit or others schemes where the phase and charge act as the conjugate variables.[9]

- Superconducting tunnel junction detectors (STJs) may become a viable replacement for CCDs (charge-coupled devices) for use in astronomy and astrophysics in a few years. These devices are effective across a wide spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared, and also in x-rays. The technology has been tried out on the William Herschel Telescope in the SCAM instrument.

See also

- Andreev reflection

- Brian David Josephson

- Cooper pair

- Fractional vortices

- Ginzburg–Landau theory

- Macroscopic quantum self-trapping

- Pi Josephson junction

- Quantum computer

- Quantum gyroscope

- RSFQ digital electronics

- Semifluxon

- Zero-point energy

- Rapid single flux quantum

- Superconducting tunnel junction

References

- ^ B. D. Josephson, "Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling," Physics Letters 1, 251 (1962), doi:10.1016/0031-9163(62)91369-0

- ^ Josephson, B. D. (1974). "The discovery of tunnelling supercurrents". Rev. Mod. Phys. 46 (2): 251–254. Bibcode 1974RvMP...46..251J. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.46.251.

- ^ The Nobel prize in physics 1973, accessed 8-18-11

- ^ P.W. Anderson and A.H. Dayem, "Radio-frequency effects in superconducting thin film bridges," Physical Review Letters 13, 195 (1964), doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.195

- ^ Dawe, Richard (28 October 1998). "SQUIDs: A Technical Report - Part 3: SQUIDs" (website). http://rich.phekda.org. http://rich.phekda.org/squid/technical/part3.html. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ Barone, A.; Paterno, G. (1982). Physics and Applications of the Josephson Effect. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471014699.

- ^ http://www.bipm.org/en/si/si_brochure/chapter2/2-1/

- ^ Fulton, T.A.; et al. (1989). "Observation of Combined Josephson and Charging Effects in Small Tunnel Junction Circuits". Physical Review Letters 63 (12): 1307–1310. Bibcode 1989PhRvL..63.1307F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.1307. PMID 10040529.

- ^ Bouchiat, V.; Vion, D.; Joyez, P.; Esteve, D.; Devoret, M. H. (1998). "Quantum coherence with a single Cooper pair". Physica Scripta T 76: 165. http://www-drecam.cea.fr/drecam/spec/Pres/Quantro/Qsite/archives/reprints/SSBox.pdf.